Urban Food Systems: GLHN-Sponsored Architecture Studio Crafts Paradigm for a Sustainable Future

Los Nopales Farmer's Market. Rendering by Andrea Riehle and Mehli Romero.

As cities in the Southwest continue to face the challenges of urban water access, rising temperatures and “food deserts”—low-income neighborhoods without access to healthy and affordable food—more and more local officials are adding food to their agendas and sustainability plans.

The University of Arizona’s Courtney Crosson, assistant professor of architecture at the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture, is committed to working with students and communities to design solutions. Over the past five years, studios led by Crosson and sponsored and advised by GLHN Architects & Engineers have focused on designing a more sustainable Tucson by 2050.

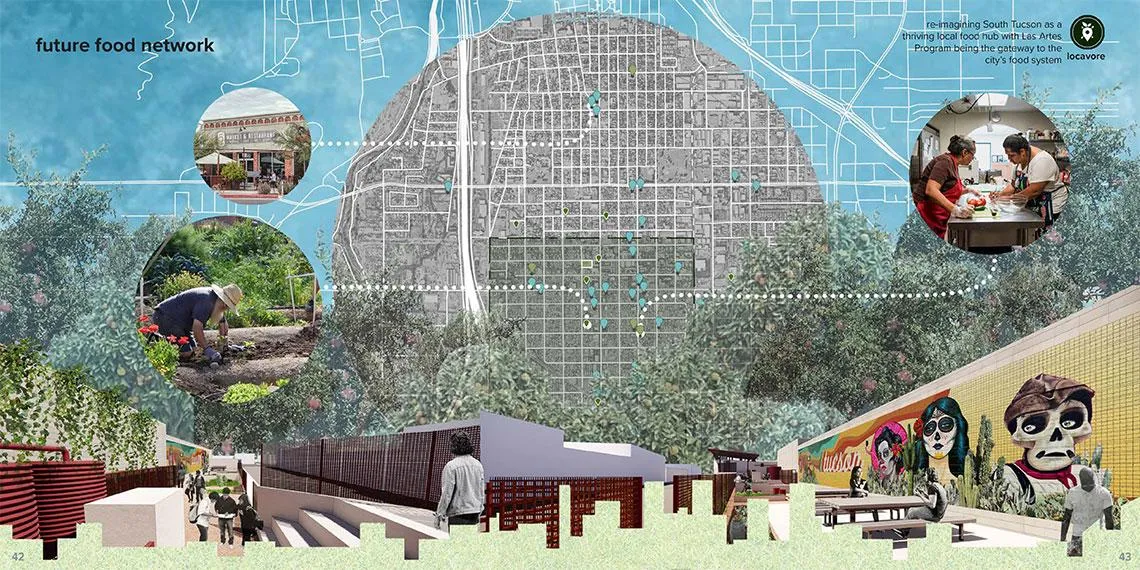

The Future Food Network of Las Artes. Image by Anisa Hermosillo and Sam Owen.

In 2017, Crosson’s students produced designs for an eco-district, followed by a future downtown in 2018 and a water-independent downtown in 2019. The final studio, held in the Fall 2021 semester, turned to the critical nexus of food-water-energy and the resulting student works are visionary designs for urban agriculture and sustainability.

Despite the region’s hot, arid climate, Tucson claims the longest continuously farmed landscape in North America, going back 4,000 years. Yet 18% of Tucson’s residents today live in food deserts. Still, one of the main takeaways for the students of the Urban Food Systems studio was that rainwater harvesting can be used to irrigate enough food to meet the needs of residents across the metro area, if designed properly.

“Cities of the future can and must be capable of providing for themselves and minimizing how much waste they produce,” says Samuel Owen ’22 B Arch, who worked on the design for Las Artes Community Food Hub, Kitchen and Garden in South Tucson. “Wherever there are concentrations of people, there’s a need to produce food and a benefit to empowering the people to do it themselves.”

Crosson’s studio was based on research she previously completed on vacant land in Tucson owned by the city and county. Her goal: determine these spaces’ ability to meet food desert nutritional demands through urban farming.

The Los Artes garden kitchen. Rendering by Anisa Hermosillo and Sam Owen

The students were tasked with designing urban food systems that rely on sustainable water sources. Student teams were paired with five community organizations: Mission Garden, Merchant’s Garden, Las Artes Arts and Education Center, Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona and Pima County Regional Flood Control District.

Each organization represented various typologies for the future of food systems in Tucson: river-adjacent (Mission Garden), community garden (Los Nopales Community Garden and Kitchen), backyard farming (Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona and Pima County Regional Flood Control District), food hub and community garden (Las Artes) and indoor-controlled agriculture (Merchant’s Gardens, a converted former school).

“Each project involved community outreach and collaboration to ensure our designs had proactive and efficient solutions to water and food systems while addressing the community’s social wellbeing, economic development and environmental protection,” says Andrea Riehle ’22 B Arch, who designed the Los Nopales Community Garden project across from the airport in South Tucson’s Barrio Nopal.

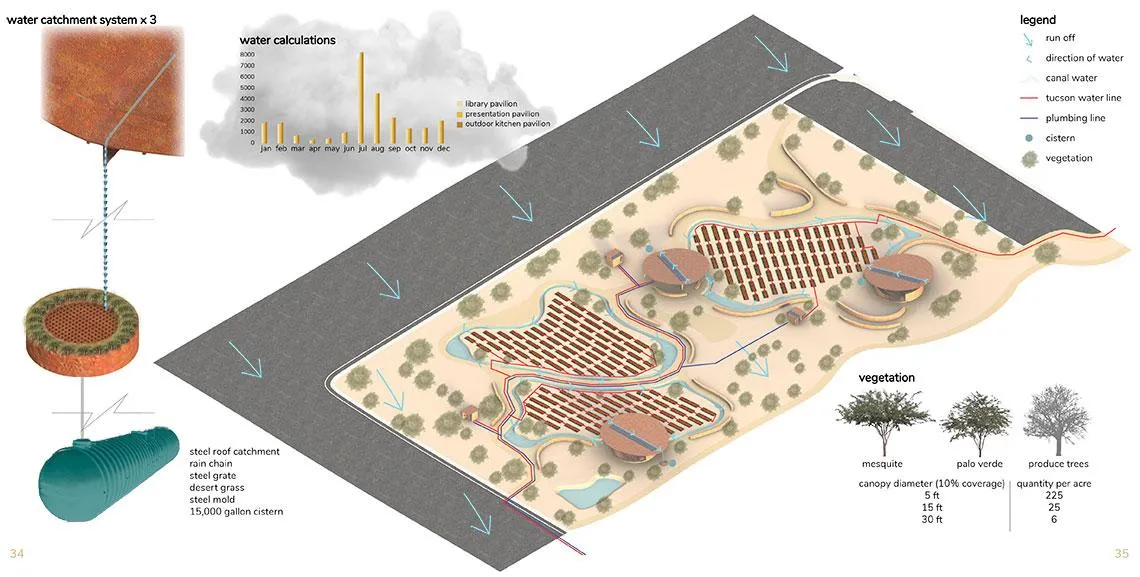

Riehle and her studio partner Mehli Romero ’22 B Arch envisioned a series of pedestrian-friendly and sustainable spaces that address food production and distribution, social equity and flooding, buffered by vegetation to keep the urban noise at bay. They designed a mix of enclosed and open spaces that include a library, presentation room, outdoor kitchen, craft space and plant nursery.

The outdoor kitchen space at Los Nopales. Rendering by Andrea Riehle and Mehli Romero.

“We developed two major water harvesting systems on the site: canals that run along the perimeter of each agriculture field and the sloped roofs of pavilions that direct rainfall into an underground cistern,” says Romero. "The canal also serves as a natural barrier to protect the crops from foraging animals while providing flood mitigation and passive irrigation.”

“When the site is running low on harvested water, it can connect to the City of Tucson’s water supply; however, to help conserve what is collected and minimize their reliance on the city, we suggested that the community gardeners focus on cultivating vegetation suitable for the desert—peppers, chilies, cactus, citrus, mesquite and so on,” says Riehle. “Since this is a Mexican-American community, the focus on edible desert vegetation is also a way to strengthen heritage connections, as these ingredients are common in Sonoran-Mexican cuisine.”

For Anisa Hermosillo ’22 B Arch and Owen, who worked with Las Artes, an aim was to help bridge the gap of food injustice within the community because Las Artes is located in a food desert.

"The inclusion of the garden kitchen allows for community members to learn how to prepare the food they have grown, adding another layer of depth in the connection between food and farm,” says Hermosillo. It also eradicates the food desert, as all the food prepared comes from the gardens onsite rather than relying on an affordable grocery store miles away.

The gardens are designed in various formats to teach students and the community diverse farming methods, from ground beds to raised beds and succulent farms.

The water catchment system at Los Nopales. Image by Andrea Riehle and Mehli Romero.

“With urbanization, the linkage between food and farm has become broken,” says Hermosillo. “We strove to reconnect how people view produce, and to rebuild the connection of appreciation between farmer and consumer. Las Artes demonstrates how thoughtful design can include everyone—students, community members, the unhoused, teachers, parents and staff.”

“The most rewarding aspect of this project was having the chance to get out of the conceptual realm of the studio and interact with a real community at a real school, gathering real data to try and address a real problem,” says Owen. “The best moments were the times we could present our community partners with our work about a place they care deeply about and be able to solicit their input and feedback.”

“We ended our project with the hopes that Las Artes is just the beginning of a rich and diverse food culture in South Tucson and the greater Tucson region,” says Hermosillo.

“There is the potential for future studio projects focused on this work,” Crosson concludes. “I plan on continuing to work with the county and other local food security advocates on funding opportunities to support the realization of these projects.”

We extend our thanks to GLHN for sponsoring four CAPLA studios focusing on Tucson 2050 since 2017. If your organization is interested in sponsoring a CAPLA studio, contact Angie Smith, director of development, at angiesmith@arizona.edu or 520-621-2608.